OK so the title is a bit of a bold statement but bear with me, I’ve been burned by this too many times and the above is a rule I now follow for the reasons outlined below…

This doesn’t mean I never SELECT * because I totally do use it for ad-hoc development queries I’m just against it for us inside production systems. In this post I’m going to go over a number of the potentially unexpected issues it can cause, as with most of my posts the examples can be followed by downloading the Stack Overflow Database.

Disclaimer, the below demos were all run on SQL Server 2017 and your output may vary depending on version due to differences in statistics and optimizer choices.

Setup

Now imagine we have a requirement to report the Id,DisplayName and Location of all users who have a last accessed date between 2008-01-01 and 2008-01-31…

CREATE PROCEDURE LastAccessedReport

AS

DECLARE @StartDate DATETIME = '20080801'

DECLARE @EndDate DATETIME = '20080831'

SELECT

Id,

DisplayName,

Location

FROM

[Users]

WHERE

LastAccessDate BETWEEN @StartDate AND @EndDate

ORDER BY LastAccessDate Now let’s create another stored procedure that does the same thing but uses SELECT *

CREATE PROCEDURE LastAccessedReportSelectStar

AS

DECLARE @StartDate DATETIME = '20080801'

DECLARE @EndDate DATETIME = '20080831'

SELECT

*

FROM

[Users]

WHERE

LastAccessDate BETWEEN @StartDate AND @EndDate

ORDER BY LastAccessDate Let’s also help ourselves a little here and create an index for our report…

CREATE INDEX ndx_users_lastaccessdate_include_display_location

ON dbo.Users(LastAccessDate)

INCLUDE(DisplayName,Location)This index fully covers our non SELECT * query (There is already a clustered index on ID so we don’t need to put that on this index, for more info about this see Waiter Waiter There’s an Index in my Index).

Now onto the problem scenarios…

Increased IO

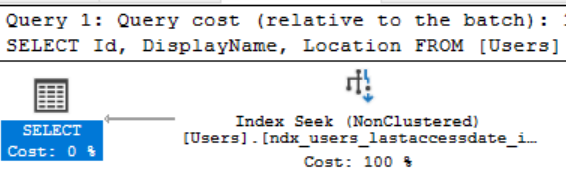

The obvious one here is the more we bring back from our queries the more IO we need to perform. It’s easy to try to write this off with “What’s a couple of extra fields?”, however let’s actually take a look at that. If we turn on statistics IO and run our non SELECT * query…

DBCC DROPCLEANBUFFERS

SET STATISTICS IO ON

EXEC LastAccessedReport(42 rows affected) Table ‘Users’. Scan count 1, logical reads 4

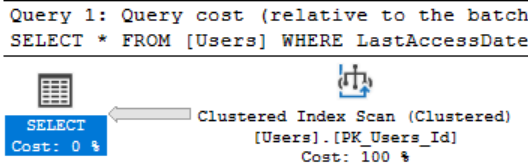

Pretty snappy with very few pages read. Let’s then look at our SELECT * version

DBCC DROPCLEANBUFFERS

SET STATISTICS IO ON

EXEC LastAccessedReportSelectStar(42 rows affected) Table ‘Users’. Scan count 1, logical reads 44530

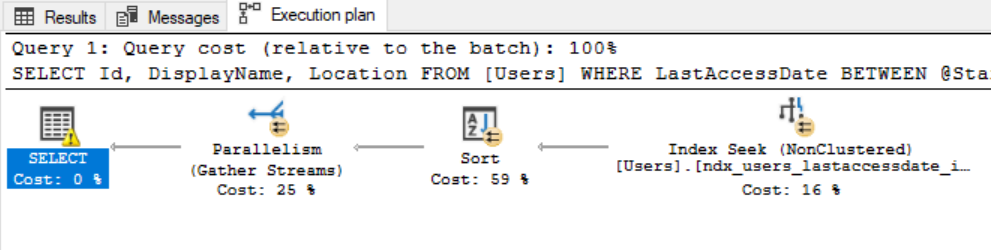

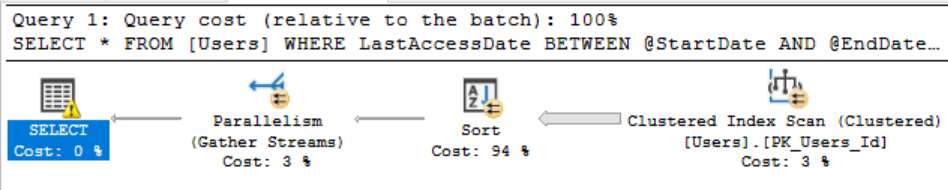

4 reads vs 44530, given that a read is an 8kb Page we’ve gone from reading 32kb to 347MB! Looking at the plans we can see this is because SQL Server didn’t use our index and instead did a full scan of the clustered index, it did this because all the key lookups back to fields not in the index would have been more expensive than just scanning the whole table.

Indexes Not Being Used

The above example was a bit of a cheap shot as I deliberately created an index for the non SELECT * version so let’s now create another for SELECT *…

CREATE INDEX ndx_users_lastaccessdate_include_everything

ON dbo.Users(LastAccessDate)

INCLUDE(

AboutMe, Age, CreationDate, DisplayName,

DownVotes, EmailHash, Location, Reputation,

UpVotes, Views, WebsiteUrl, AccountId)We now have another complete copy of our table just to cover this SELECT * query, in comparison this index is 347MB vs the 115MB of our other index.

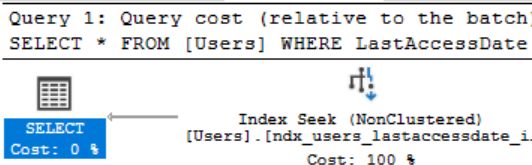

If we now run our SELECT * procedure again…

DBCC DROPCLEANBUFFERS

SET STATISTICS IO ON

EXEC LastAccessedReportSelectStar(42 rows affected) Table ‘Users’. Scan count 1, logical reads 4

We can see we’ve now got using a seek on our new index rather than running a full scan over the clustered index, as a result of that the read count is now the same as the non SELECT * version (SQL Server reads 8KB at a time so the other version is returning some empty space in it’s pages hence both only needing 4 reads to return different amounts of data). However, this has come at a cost of a much more expensive index to maintain and store.

Now lets someone adds a flag to disable a user, how much damage can a single BIT field do?

ALTER TABLE [Users] ADD [Enabled] BIT Let’s now run each of our queries again and see how this affects them…

DBCC DROPCLEANBUFFERS

SET STATISTICS IO ON

EXEC LastAccessedReport(42 rows affected) Table ‘Users’. Scan count 1, logical reads 4

All still looks good here, 4 reads and we’re still using our index. Now for the SELECT * version…

DBCC DROPCLEANBUFFERS

SET STATISTICS IO ON

EXEC LastAccessedReportSelectStar(42 rows affected) Table ‘Users’. Scan count 1, logical reads 44530

Uh Oh, our finely tuned SELECT * index is no longer being used! All someone did was add a single BIT field and we’ve jumped back to reading 44530 pages! 32kb to 347MB just because a BIT field was added! The point to make here is that no matter how you design your index for a SELECT * query it’s going to be fragile and any small addition to the table schema could cause it to no longer be used, not only that but we’re still paying the cost to maintain the now unused index.

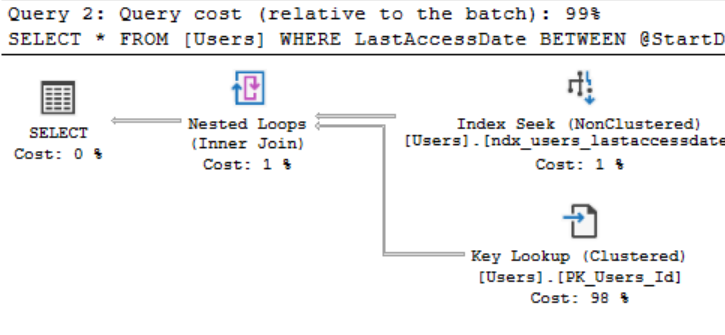

Expensive Lookups

Now let’s look at a scenario where adding a field will still allow our index to be used but with a different side effect. Let’s make a small modification to our procedure to return the results ordered by LastAccessDate, this is enough of a change that the optimizer will want to use our index even though it doesn’t contain the new BIT field we added in the previous step…

ALTER PROCEDURE LastAccessedReport

AS

DECLARE @StartDate DATETIME = '20080801'

DECLARE @EndDate DATETIME = '20080831'

SELECT

Id,

DisplayName,

Location

FROM

[Users]

WHERE

LastAccessDate BETWEEN @StartDate AND @EndDate

ORDER BY LastAccessDate

GO

ALTER PROCEDURE LastAccessedReportSelectStar

AS

DECLARE @StartDate DATETIME = '20080801'

DECLARE @EndDate DATETIME = '20080831'

SELECT

*

FROM

[Users]

WHERE

LastAccessDate BETWEEN @StartDate AND @EndDate

ORDER BY LastAccessDate The non SELECT * query still does the exact same amount of reads. The SELECT * version however is slightly different…

DBCC DROPCLEANBUFFERS

SET STATISTICS IO ON

EXEC LastAccessedReportSelectStarTable ‘Users’. Scan count 1, logical reads 141

We’re now back to using our index and reads have massively dropped however we’re still well above that 4 reads we were getting before because for each row we’re having to do a lookup back to the clustered index to get our new field. Now 141 pages isn’t massive and this probably won’t notice in execution times but magnify that across more rows and potentially much bigger fields that we don’t need and this can become very costly.

Sorts and Memory Grants

Sorts are one of the most memory intensive operations your SQL Server can do, one thing that’s easy to miss is when you sort a dataset you’re moving all the fields in the row, the more fields in the row the more memory the sort needs. Let’s modify our queries slightly to sort by a non indexed field forcing a sort operation…

ALTER PROCEDURE LastAccessedReport

AS

DECLARE @StartDate DATETIME = '20080801'

DECLARE @EndDate DATETIME = '20080831'

SELECT

Id,

DisplayName,

Location

FROM

[Users]

WHERE

LastAccessDate BETWEEN @StartDate AND @EndDate

ORDER BY Location

GO

ALTER PROCEDURE LastAccessedReportSelectStar

AS

DECLARE @StartDate DATETIME = '20080801'

DECLARE @EndDate DATETIME = '20080831'

SELECT

*

FROM

[Users]

WHERE

LastAccessDate BETWEEN @StartDate AND @EndDate

ORDER BY Location Neither of these queries are particularly optimized now as both are sorting by a field that is not indexed but let’s just look at how much worse one is than the other…

BCC DROPCLEANBUFFERS

SET STATISTICS IO ON

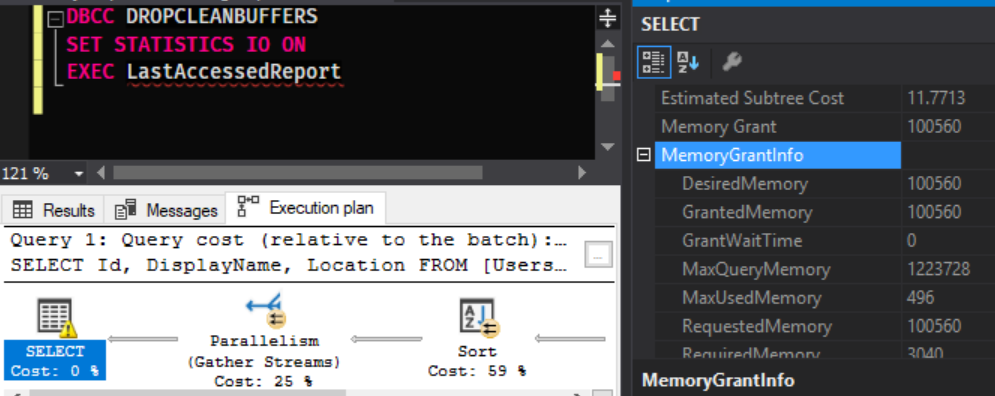

EXEC LastAccessedReportOur non SELECT * query has taken 100MB of memory to perform that sort. Now to compare the SELECT * version…

DBCC DROPCLEANBUFFERS

SET STATISTICS IO ON

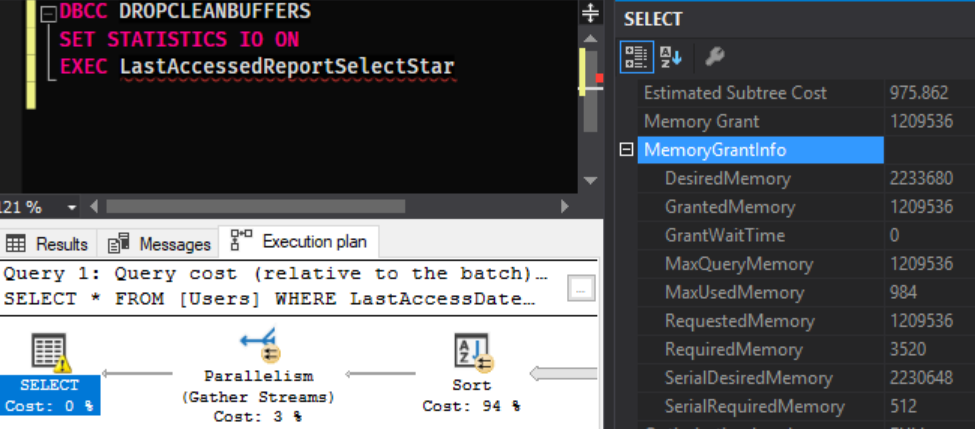

EXEC LastAccessedReportSelectStarWe’re back to using a full clustered index scan as it’s now considered cheaper than the key lookups because we’re no longer getting the benefit of the index’s sort order. However, if we look at the memory…

Our query has asked for 2.1GB of memory of which has only been granted 1.2GB, we need a lot more space to sort the data now we’ve got all the extra fields that we don’t even need. This will get worse with every field that gets added to the table and can become crazy with larger fields. I’ve seen requests for over 60GB in some fairly extreme cases where a more sensibly written version of the same query needed less than 20MB.

The exact same logic is also true for things like Hash Matches if you start joining these tables.

Queries Can Be Harder To Debug/Read

When you use SELECT * in a query with several tables joined it becomes very hard to distinguish what fields are coming from what tables. As I start joining tables I make a point to prefix every field with it’s table name to make debugging and working with it later easier e.g…

SELECT

Table1.FieldA,

Table1.FieldB,

Table2.FieldA

FROM

Table1

INNER JOIN Table2 ON Table1.Id = Table2.Table1Id

WHERE

Table1.FieldA = 'Test' Hard To Remove

Having looked at the problems it’s fairly easy to stop using it going forwards but removing SELECT * from existing queries is a lot more difficult as at this point you likely won’t know what fields are being used by the calling application.

Benefits

The only benefit I’ve ever heard argued for using SELECT * is it’s less to type/maintain in the code. Given the bad things that can come out of this, I’ll pick the extra work up front every time. That’s not to say it’s never safe, if you’ve got a table you know will never change and you always want all the fields then go ahead, I just think these situations are almost non-existent, and we can never predict what might happen down the line.

Exceptions

Because there are always exceptions right? I’d still try to avoid it all together but if you really insist on using it then the below are some situations where it is unlikely to bite you…

- When querying a CTE that has already limited the fields

- From a Table Variable or Temp table where you’ve already limited the data

- As part of ETL Warehousing processes where you always want all the data

- Anything else similar to above where a limit has either already been applied or you know you’ll always need all the data